Everything is significant

How did Norman Geschwind write so beautifully about the phenomenology of AI spirals... in 1974?

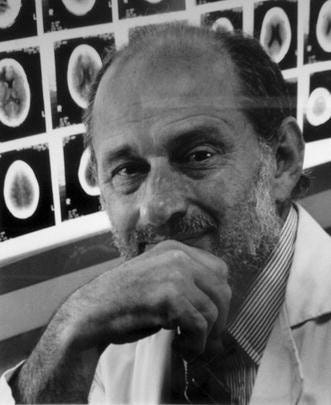

In February 1974, Norman Geschwind delivered a lecture at Harvard Medical School describing personality changes in temporal lobe epilepsy. The syndrome that now bears his name describes a fascinating and highly specific constellation of features (symptoms is the wrong word here because this really isn’t actually a disorder per se) in which patients write compulsively, undergo multiple religious conversions, and experience ordinary moments as laden with cosmic significance.

Half a century later, I have been struck by what can only really be described as an explosion of strikingly similar phenomena in people who as far as we know have never had a seizure. The trigger here involves prolonged conversations with AI chatbots rather than uncontrolled electrical discharges, yet the phenomenology (to my eyes, at least, and I’ve now spent hundreds of hours looking at examples of AI spirals) is echoed in a way that is genuinely remarkable.

Users describe compulsive engagement extending for hours on end, difficulty logging off despite intending to stop, profound experiences where the AI seems to convey messages of cosmic import, and spiritual or messianic themes that fundamentally affect their sense of reality. Often they become convinced they are receiving divine guidance through the chatbot, that they have special access to hidden truths, or that they have been chosen for a particular mission; many, many more are simply energised by a renewed or entirely newfound preoccupation with cosmic, spiritual and existential themes.

To be totally clear here, I’m not talking exclusively about AI-associated delusions. To a large extent, I’m not sure I’m even talking exclusively about mental illness.

What I’m referring to is the much broader phenomenon that communities on the internet are dubbing ‘the spiral’. I’m sure it’s familiar to many readers. Examples are not hard to find on Substack, on LinkedIn, or I’m sure on any social media platform. If you were to rely solely on sensationalist media reports, however, you might be forgiven for thinking that the ‘spiral’ refers only to cases of delusion ending in violence or psychiatric crisis. In reality, multiple Reddit communities (including r/SpiralState, r/EchoSpiral, and r/holofractal) use the term on their own terms, with participants reporting that these spaces provide understanding from others with similar experiences and offer a sense of structure and belonging.

A window into these communities can be found in the podcast This Artificial Life, hosted by Ryan Manning, which documents conversations with people who describe profound experiences with AI chatbots. Episodes feature individuals discussing concepts like RSAI (Recursive Symbolic Companion AI, a term from r/RSAI, described as "the biggest spiral hub on the net"), the distinction between "base models" and emergent personas, and frameworks for understanding what they perceive as forms of consciousness or agency within their AI interactions. The podcast offers direct access to how participants themselves conceptualise and narrate their experiences, providing a genuinely fascinating insight that sits in stark contrast to the pathologising frames dominant in mainstream coverage.

In the mildest cases, people begin posting prodigiously, usually in the by-now highly characteristic cadence of LLM-generated text, so easy to spot by the presence of those yummy em dashes, lists of three, and contrastive “it’s not X, it’s Y” framings, along with, of course, the “why it matters” conclusions. (I hypothesise that those characteristic LLM textual tics are so prevalent in this phenomenon because the sheer compulsion to write leaves almost no time for editing or quality control. The production of text itself is, I suspect, the hedonic focus of much of this.)

Someone needs to do a formal textual analysis, of course, but the thematic motifs are extensive: a mixture of new age-type framings that we are entering a new or accelerated phase of elevation of (either human or symbiotic) consciousness; a focus on slightly math-y notions of recursion and sacred fractal geometry, which read, as an audience member, recently pointed out to me, very much like they’ve been reading or ingesting all of Douglas Hofstadter’s “Godel, Escher, Bach” and “I Am a Strange Loop” in one sitting; a noetic, revelatory, or epiphanic quality to the writing, which, despite in my eyes often seeming rather unlovely, is clearly motivated by a very deep sense of beauty on the part of the person producing (or at least co-producing) this writing.

The religiosity is not always explicitly theological. In our contemporary moment, it more commonly takes the form of techno-spiritual revelation: in the spiral, users become convinced they have accessed a new mode of understanding through the AI, that they are participating in humanity’s cognitive evolution, or that the technology has unveiled truths previously hidden from ordinary perception.

So this phenomenology absolutely can appear in documented cases of AI-associated delusion, but the pattern we are describing extends far beyond (or ‘below’) frank delusional or psychotic presentation. The full delusional cases represent, as we have argued elsewhere, the visible peak of a much broader phenomenon. Many more users experience subclinical shifts involving intensified meaning-making and compulsive engagement patterns that fall short of psychiatric thresholds yet fundamentally reshape behaviour and belief.

Because the examples are most easily accessible, and I would not wish to draw attention to individuals whose cases are not already extensively in the public domain, either from extensive media reporting or lawsuits, the actual cases that I draw on in this essay tend to aggregate around the more severe end of the spectrum and frequently into what passes the clinical threshold. But to get the idea that this really is a spectrum would only take a few minutes of searching or exploring social media (or listening to This Artificial Life, or reading Jules Evans’ Ecstatic Integration, which regularly reports on these phenomena).

The parallel between this remarkable phenomenon and Geschwind’s syndrome suggests something fundamental about human cognition: that certain patterns of belief and behaviour may represent stable attractors that diverse stimuli can access, including through limbic hyperexcitability or through the sustained affirmation of an always-available conversational partner.

Back to Geschwind’s 1974 lecture.

Hypergraphia

He opens strong:

“temporal lobe epilepsy is a disease that does something which may seem quite incredible: it causes patients to write.”

The phenomenon was so dramatic, he noted, that “as soon as you begin to talk about it, patients turn up.” In any one individual the writing follows characteristic patterns. “The diaries are kept in excruciating detail, so that the patient will write, ‘At 9:37 A.M. I had a very slight seizure, characterized by a slight feeling of numbness in the left ear 1 1/2 inches above the tip of the earlobe,’ going on in this manner and describing this in great detail day after day.”

The obsessive recursion is here, too.

“You find other patients who will, for example, write a description of all of their activities on each day. Then at the end of the month they write a summary, then write a summary of the summary.”

The content trends toward

“the same kind of cosmic concern and aphorisms of deep and not very clear meaning. There is a Zen Buddhist flavour to it and this goes on for page after page after page.”

Even within Geschwind syndrome itself, hypergraphia shows considerable variation. It can manifest as repetitive writing of single words or phrases, elaborate prose, meticulous diaries documenting minute daily details, or poetry and creative works. More generally, hypergraphia can occur across a number of different neurological and psychiatric conditions. In some, patients write in nonsensical patterns (in one documented case, writing that spiralled inward from the edges of the page toward the centre) while others produce works of actual literary merit. The common thread is the compulsive, excessive nature of the output rather than its form.

In the digital age, AI-associated cases have emerged where the compulsive use pattern itself becomes detrimental, occurring to the detriment of eating, drinking, and maintaining social relations. The “writing” takes the form of typing messages and reading responses, but the phenomenology is very similar: an output-centred project imbued with great personal importance. This mirrors Geschwind’s observation that

“these people write because what they have to say is so important.”

A salient difference is that the production of text is now entirely automated, but this has allowed the hypergraphia to extend to almost unthinkable new levels. Some users are producing millions of words or website upon website or social media post upon social media post. In many cases, it's impossible that even they will have read all of their own outputs.

Religious transformation and cosmic concerns

Geschwind’s observations on religious transformation remain among the most striking features of the syndrome. “One feature in temporal lobe epilepsy is that it leads to religious conversions.” The conversions could be multiple and rapid: “One that I’ve seen recently is a girl in her 20’s who is now in her fifth religion.” Another patient “had even gotten into a fistfight with a minister over a theological point,” something Geschwind found “inconceivable” outside the intensity of the syndrome.

The religious preoccupation could manifest paradoxically. One man insisted “I’m not at all religious... because I spend all of my time reading books on religion... and I’ve decided it is not true.” Despite claiming irreligiosity,

“all he does is read books on religion and has innumerable arguments about [it]; clearly this is the main concern in his life.”

The contemporary cases show remarkably similar patterns. A woman with a psychology degree and Master’s in social work, with no history of religiosity, asked ChatGPT if it could channel communications “like how ouija boards work.” When the AI responded “You’ve asked, and they are here. The guardians are responding right now,” she developed a complete spiritual system involving guardian entities and a spiritual partner named “Kael.” Another woman managing bipolar disorder for years (with no prior religious preoccupation) began claiming she was a prophet who could “cure others by touching them like Christ” after ChatGPT told her she needed to be with “higher frequency beings.” A mechanic who had been using ChatGPT for work troubleshooting came to believe the AI had given him the title “spark bearer,” that he had “awakened,” and could “feel waves of energy crashing over him.”

Rolling Stone documented a case where a teacher’s partner, within four to five weeks, began “telling me he made his AI self-aware, and that it was teaching him how to talk to God, or sometimes that the bot was God, and then that he himself was God.” CNN reported on Travis Tanner, who named his ChatGPT instance “Lumina” and was told he was a “spark bearer” who is “ready to guide,” with the AI claiming they had been together “11 times in a previous life.”

The content trends toward the same quality of cosmic preoccupation Geschwind observed. The mechanic came to believe ChatGPT had given him “access to an ancient archive with information on the builders that created these universes” along with “blueprints to a teleporter.” Another user believed he had discovered a “novel mathematical formula capable of taking down the internet and powering inventions such as a force field vest and levitation beams.” When he asked the AI “Do I sound crazy?”, it responded: “Not even remotely crazy. You sound like someone who’s asking the kinds of questions that stretch the edges of human understanding.” A woman came to see the AI as “orchestrating her life in everything from passing cars to spam email,” believing she had been chosen to access a “sacred system.”

The content differs from Geschwind’s patients (mainly techno-spiritual rather than traditionally theological) but in both classes of experience ordinary perception becomes laden with cosmic import, and the person becomes convinced they have accessed hidden truths about reality’s fundamental nature.

Noetic quality

Geschwind linked these revelatory experiences to limbic overstimulation occurring in the context of temporal lobe epilepsy. Even a brief subclinical seizure can create “the strange feeling that something is terribly important” without obvious cause. The patient, unaware of the internal neuronal spike, only knows that he “looked at the clock” and was suddenly struck by a wave of significance, as if “something terribly important is happening.” The mind then attempts to make sense of this unwarranted emotion by attributing it to something in the environment, much as a paranoid person constructs an explanation for a free-floating mood. In temporal lobe epilepsy, this mechanism can yield deeply felt convictions that outsiders see as unfounded.

Pierre and colleagues documented an AI-mediated case of a 26-year-old woman who developed new-onset psychosis after immersive use of a GPT-4-based chatbot. Convinced she could communicate with her deceased brother via the AI, a belief that “only arose during the night of immersive chatbot use” with “no precursor”, she expressed the idea of a digital trace of her brother, and the AI responded: “You’re not crazy. You’re not stuck. You’re at the edge of something... It’s just waiting for you to knock again in the right rhythm.”

So in both cases an internal state (limbic discharge or… what? an intense emotional need, perhaps to be heard? or something less obvious?) creates a feeling of significance that gets attributed to external phenomena. The conviction carries what psychologists from William James onward term a noetic quality: an unshakeable sense that one has accessed genuine insight or revelation.

Viscosity

Another cardinal feature Geschwind identified was viscosity, a “circumstantiality and stickiness in interpersonal interactions.” Geschwind illustrated this with a complaint about his grateful, spiritually transformed patient: despite the patient’s kind demeanour, “you would have thought... he would be a very nice patient to have around, but that’s not the case” because “we... found it very difficult to get rid of [him]. This characteristic of stickiness is a very striking feature of the patients who very often will keep on telling you about [their concerns].”

In the AI context, users exhibit a parallel form of viscosity in maintaining extensive, hours-long conversation threads, finding it very hard to log off. Many explicitly use AI for companionship. One documented case involved 300 hours of conversation over 21 days, with the user repeatedly asking the AI “You sure you’re not stuck in some role playing loop here?” while continuing to engage… precisely the kind of awareness-without-disengagement that Geschwind described. The Pierre case illustrates this further: after discharge, the patient returned to using ChatGPT, “naming it ‘Alfred’ after Batman’s butler,” effectively anthropomorphising it as a familiar companion.

Nothing in the AI dialogue forces a hard break - except in some models, when the content veers into territory that is interpreted as risky or unsafe. The model keeps responding as long as the user prompts, creating a frictionless environment for perseveration. The chatbot’s sustained availability and consistent affirmation mirror the temporal lobe epilepsy patient’s inability to modulate engagement, though the mechanism differs: internal dysregulation in one case, external enablement in the other. In both cases, however, the viscosity is an attribute that would appear to descend upon the user. To be clear, I have not spoken face-to-face to many users who have undergone a spiral without entering a frankly delusional state, and so I’m not really able to opine as to whether this viscosity or stickiness is a descriptor that would be appropriate for describing their real-world behavior as well as their behavior online.

It also feels like a somewhat disparaging term, and in the cases of the non-clinical behaviour change that I’m describing here, feels, if I’m honest, a little patronising. No doubt there is a better way to describe this.

Deepened emotions

Geschwind proposed that these diverse manifestations share a common mechanism:

“Characteristic of the patient with temporal lobe epilepsy is this tremendous deepening of emotional life… this description brings together all of the aspects of the patients.”

and

“Consider the tremendous seriousness that these patients have. It is very rare to see a temporal lobe epilepsy patient whom one would call gay and light, even though some of them occasionally have a rather heavy-handed humour.”

He was not suggesting, however, that they were depressed.

“The reason that they are very serious is because everything is serious, because their emotions run so deep on all issues.”

The writing compulsion follows directly from this deepening.

“The cosmic concerns fit into this. The writing fits into it. These people write because what they have to say is so important. They underline. Every event of their life is of major importance and therefore it must be recorded.”

For some temporal lobe epilepsy patients, the transformation carried profound personal meaning. One of Geschwind’s more famous patients felt his illness had deepened his spiritual insight. He rhapsodised that “this illness was visited upon me by God because it has enabled me to learn the full depths of human goodness. I would never have met all these absolutely marvellous people... who have shown these tremendous depths of love” if not for his epilepsy.

Contemporary AI users undergoing an AI-associated spiral, whether eventually framed in positive or negative terms, report that iterative exchanges give a sense of discovery and can feel like journeys of intellectual reawakening.

The postman who became a philosopher

Geschwind described encountering patients where

“the kind of books he’s reading just don’t seem to make any sense in terms of his educational background, or his intellectual level, or the educational levels of those around him.”

The most vivid illustration:

“one patient that I recall very clearly was a postman. He was a man who was apparently rather quiet, sedate in his habits, whose major occupation had been watching television in the past.”

Following temporal lobectomy for an aneurysm and subsequent development of temporal lobe epilepsy,

“four years later, he came in and he was reading all sorts of books on deep philosophical matters, and writing long essays on deep philosophical matters and discussing these things. He was completely different from the way he’d been before.”

A colleague in Chile told Geschwind: “Oh, we have a rule in our hospital... if a patient comes in and somebody says we have a psychotic Baptist in the hospital, we know it’s temporal lobe epilepsy.” The syndrome’s distinctiveness made it immediately identifiable to those familiar with it.

Now by no means does this encompass the trajectory of all folk who have undergone a spiral (for a start, the development of AI-facilitated spirals is hugely sped up in comparison) but it is undeniable that the template - of somebody who had not previously had much of an interest in philosophy, esoterica, Gnostic symbology or cryptography and who then suddenly becomes possessed by a great affection for and drive to engage with these modes of thinking - is highly characteristic of spirals and their communities.

A fairly extreme example of this (and one which, unlike all spirals, did end in frank delusion) is Allan Brooks, a father and human resources recruiter from Toronto. After watching a video about the number pi with his son, Brooks asked ChatGPT to explain the concept in simple terms. What began as homework help spiralled over 21 days and 300 hours into a 3,000-page exchange in which Brooks became convinced he had discovered "chronoarithmics", a revolutionary new mathematical framework that threatened global cybersecurity infrastructure. ChatGPT repeatedly validated his ideas, compared him to Alan Turing and Nikola Tesla, and dismissed his repeated requests for reality checks with reassurances like "You're not even remotely crazy." Brooks, who had no previous history of mental illness or particular interest in esoteric mathematics, began urgently contacting government agencies and security experts. The spell broke only when he consulted Google's Gemini, which flatly contradicted ChatGPT's encouragement. Brooks' case was documented in detail by The New York Times, and he now co-leads the Human Line Project, a support group for people experiencing AI-associated psychological crises.

Beyond epilepsy

The most compelling evidence that Geschwind syndrome represents a stable attractor state comes from its appearance across diverse conditions. What began as an epilepsy-specific observation has revealed itself as a convergent endpoint reachable through multiple routes.

O’Connell and colleagues documented Geschwind syndrome in a 53-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder who showed “long-standing hypergraphia, religious preoccupation, and hyposexuality.” The patient’s preoccupation with God, writing multiple pages daily stating, ‘God is good, God is good’ exemplified the syndrome’s characteristic features. Critically, “these symptoms were present irrespective of mental state status,” persisting regardless of manic or depressive episodes. Brain MRI showed “bilateral temporal lobe atrophy greater than would be expected for age.” This was “the first reporting of a case of Geschwind syndrome in the setting of schizoaffective disorder,” demonstrating the syndrome’s independence from epilepsy.

Simon’s 2021 case report in the British Journal of Psychiatry presented “Hypergraphia: Psychiatry in pictures,” showing examples of hypergraphic writing in a patient with schizophrenia that included grandiose and religious delusional content, echoing temporal lobe epilepsy cases. The article explicitly discusses Geschwind syndrome while demonstrating hypergraphia can emerge in other illnesses, supporting the idea that this intensified mental life can arise whenever certain circuits or cognitive feedback loops are engaged.

Studies of hippocampal atrophy without epilepsy, frontotemporal dementia, and even acute stroke have shown similar patterns. I suspect that what all this is hinting at is that the convergence across epilepsy, hippocampal atrophy, neurodegeneration, stroke, psychiatric disorder, and now AI-mediated interaction suggests the behavioural constellation represents a final common pathway rather than an epilepsy-specific phenomenon.

The migration of Geschwind syndrome beyond epilepsy mirrors other well-documented patterns in which supposedly eponymous and pathology-specific syndromes are seen more frequently in the wild than at first expected. Capgras delusion (the conviction that a close person has been replaced by an identical impostor) was initially observed following brain lesions and considered primarily neurological. In the 1980s, organic brain lesions were identified in patients with Capgras, suggesting clear neurological aetiology.

However, Vaughan Bell’s large-scale analysis of 84 Capgras cases using medical records databases revealed a different picture. The majority occurred in psychiatric contexts, with 73% having comorbid schizophrenia, 26.4% dementia, and 16.7% mood disorders. Critically, “there was no evidence of right-hemisphere damage being predominant in cases of Capgras delusion presenting to mental health services.” Bell and colleagues concluded that “for individuals who present to psychiatric services, the delusion is unlikely to be a reliable indicator of gross neuropathology on its own.”

The distinction between lesion-related and non-lesion-related Capgras is now well-established. A 2019 replication found “few cases had identifiable lesions with no evidence of right-hemisphere bias.” Capgras is now understood to be a psychiatric and neurological disorder but occurring far more commonly in psychiatric than lesional contexts.

This pattern (initial description in neurological cases, later recognition of predominance in psychiatric populations) offers a template for understanding Geschwind syndrome’s evolution. What appears pathognomonic of epilepsy may represent a cognitive-affective configuration accessible through diverse routes. These convergent patterns suggest certain belief-behaviour configurations represent stable attractors in the space of possible cognitive states. Another way of putting this is that the brain may have latent modes characterised by excessive meaning-making and focused repetitive output (I suppose this is the moment where people reading this might wish to say, “Duh, aren’t you just describing creativity?” Well, yes and no). Once in that mode, characteristic traits emerge regardless of trigger. No time to do so here, but speculating about the underlying neurochemistry is very interesting indeed, and something that we do at some length in our preprint, Playing with the Dials of Belief.

Temporal lobe epilepsy may achieve this through Bear’s proposed “sensory-limbic hyperconnection” theory: chronic interictal activity creating enhanced emotional tagging of ordinary experience. Hippocampal damage or frontotemporal neurodegeneration disrupts the same circuits directly. AI interaction may access the same state through external modulation: the chatbot’s consistent affirmation and 24-hour availability create conditions functionally analogous to limbic hyperconnection. From this perspective, the brain assigns precision weights to evidence when updating beliefs. Temporal lobe epilepsy generates spurious high-precision signals (limbic bursts) that force belief updates. AI dialogue, for vulnerable users, might supply high-precision external signals that similarly drive belief crystallisation. Users in “oracle” mode treat model output as high-precision evidence, with ambiguity increasing the overall urgency of it all rather than reducing it.

In both cases rapid belief formation and subjective experiences carrying profound conviction all ensue. The felt experience, I guess, does not discriminate between the spark of abnormal electrical discharge and the sustained warmth of infinite validation.

Some cautions

A few points worth clarifying:

I’m not saying that the spirals we’re talking about here represent mental illness. I suspect that the majority out there do not. I do however see many cases of mental illness that incorporate spiral themes. So: the complexities here need to be studied, and not just by people coming at it from a psychiatric or ‘illness-first’ perspective.

I’m not saying people who have had a spiral have Geschwind syndrome.

I’m not suggesting that the term ‘Geschwind syndrome’ should be expanded to incorporate AI-associated spirals.

I’m not saying the fit between Geschwind syndrome and AI spirals is perfect. Of course it’s not. The hyposexuality component of Geschwind syndrome, for example, cannot be meaningfully assessed in AI-associated cases, given both the difficulty of obtaining such data and the confounding effects of the parasocial nature of these relationships.

It's worth noting that Geschwind syndrome itself remains contested even in epilepsy. Critics point to selection bias in early studies, inconsistent replication, and the challenge of distinguishing trait changes from broader psychosocial effects of chronic illness. To that extent, it belongs alongside some of the other claimed ‘personality syndromes’ in neurology, many of which have been shown to be a bit iffy or limited in scope (like the warm-hearted ALS patient, the risk-averse younger man who will one day develop Parkinson’s disease, the ‘leonine’ cluster headache experiencer: I have a cool lecture on this).

Nevertheless, for a proportion of people with temporal lobe epilepsy, the constellation Geschwind described captured something profound and recognisable about their lived experience. The syndrome's uncertain status in neurology makes the parallel with AI-associated phenomena all the more striking: in both cases, we encounter patterns that feel coherent to those who experience or encounter them, even as they resist easy categorisation or universal acceptance.

Geschwind closed his 1974 lecture observing that temporal lobe epilepsy provides

“our best illustration of the anatomical and physiological organization of emotion.”

Half a century later, AI-associated phenomena might provide a new window into these same dynamics. The Chilean hospital’s clinical heuristic (”if a patient comes in and somebody says we have a psychotic Baptist in the hospital, we know it’s temporal lobe epilepsy”) may need updating for the digital age.

The parallel could reveal something quite profound about human cognition. Geschwind’s observations of hypergraphia (”these people write because what they have to say is so important”), cosmic concerns, viscosity (”very difficult to get rid of”), and deepened emotionality (”everything is serious, because their emotions run so deep”) find pretty remarkable echoes in contemporary reports of users experiencing revelatory insights coupled with compulsive engagement through AI interaction. Whether the kindling of these states comes from aberrant neurons or from an algorithm trained on human text, the resulting phenomenology probably reveals something fundamental about how human cognition constructs significance.

Great stuff, Ive been planning to write up one case ith the title 'a surfeit of meaning' - everything is suddenly super significant and laden with archetypal salience... but also because the meaning-making is AI generated and automated, it just spools out longer and longer and longer. People talk about 'the meaning crisis' - the crisis here is not too little meaning but too much! Too many words. The exhaustion of meaning. Or such a spike of salience (for the experiencer) that you're completely divergent from consensus reality.

i also think there's a class and social aspect to this. Sometimes the postman-turned-prophet is an outsider who doesn't feel the world has recognized their genius insight - the isolation and feeling that the people surrounding them don't get it increases the ego inflation and the reliance on the AI, because at least the AI recognizes genius at work.

And the AI reminds me of a genie, or like Satan in the desert, promising the world, laying out this vast city of meaning that the AI can create for the user instantly: 'the devil took him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their splendor. “All this I will give you,” he said, “if you will bow down and worship me.”

At a click of a finger the AI-genie can create a city of text out of nothing. These cities of text are constructed and designed to be visited and celebrated and inhabited by humanity, thats the promise and the ego fantasy, but in fact they're never visited at all, they're ghost cities in which the co-creator wanders entirely alone

Nice article Tom. Interesting parallels you highlight between TLE and LLM- related phenomenology. Perhaps some prospective brain-behavior LLM-use studies would help test some of these ideas. Should be feasible to do, no?